Imbi: Body Image and Representation

- Aug 30, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 20, 2020

By Emma Volard, Jake Amy, Hugh Heller and Ella Clair

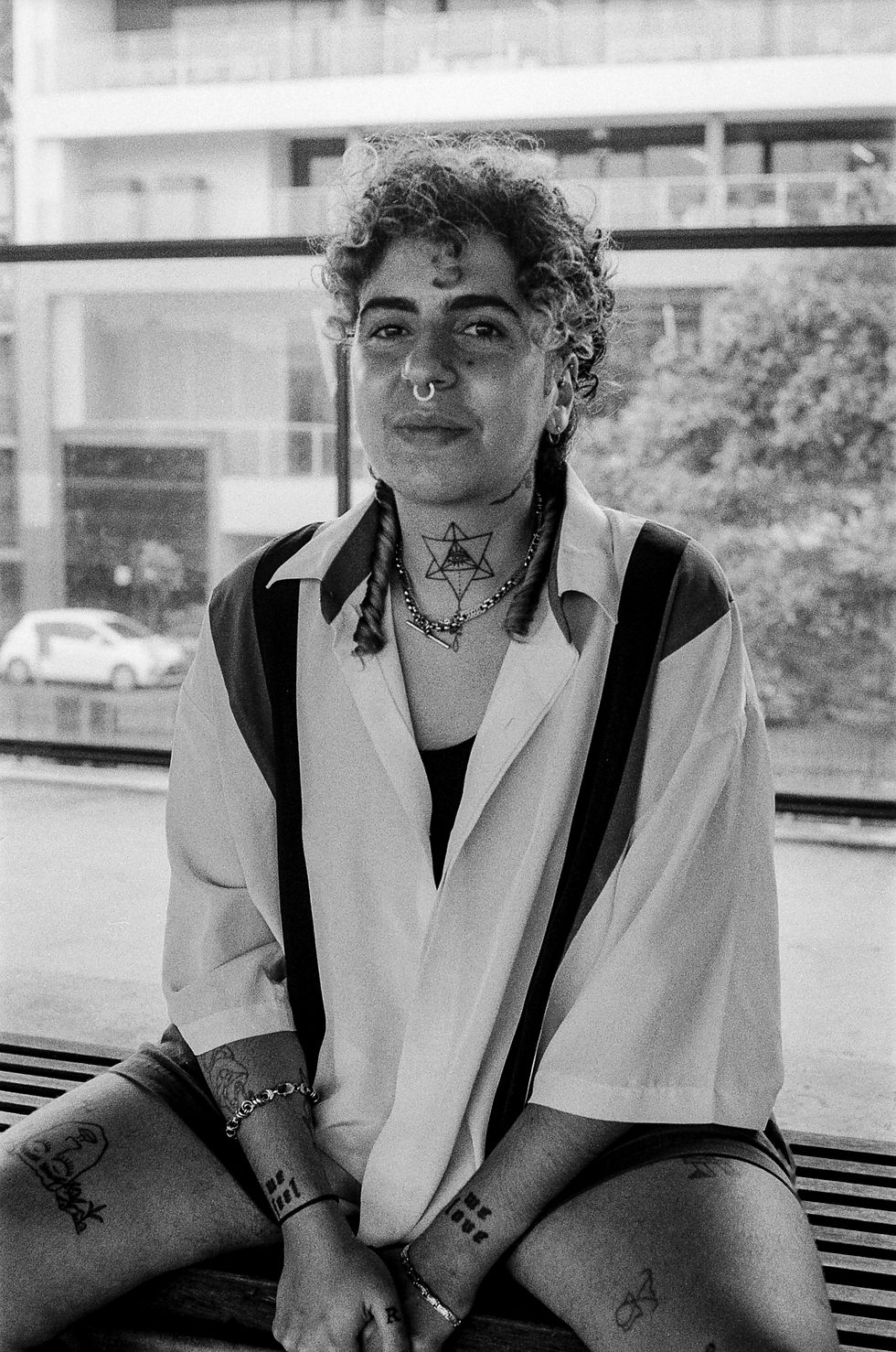

In this moment of increased online discourse surrounding the nuances of cultural and gender identities, music artists have been at the forefront of the conversation. For people who don’t fit within societal "norms", their real life experiences preceded this dialogue. Alternative RnB artist Imbi has paved a path for such people in our music industry, but not without difficulties. Imbi expresses that all personal and political matters are deeply connected. To them, body image intersects with these other facets of identity. In a chat with Emma Volard last week, Imbi displayed hope for a genuinely diverse and inclusive music industry. What follows is an abridged version of this conversation.

Can you talk about your relationship with your body?

As with any relationship, my relationship with my body is incredibly complex and very fluid - it’s ever-changing, growing and developing. Right now, it’s a mostly positive one. I feel that each day I grow more and more into myself, and feel more and more peaceful with my vessel. But that being said, it fluctuates. And my relationship with my body isn’t exclusive to me. When I have people around me who are telling me I’m beautiful and sharing joyful moments with my body, it helps me affirm my relationship with my body. That’s an energetic exchange.

How has your identity impacted your perspective on body image?

For a long time, I deeply resented myself and my body, and I didn’t understand why. I thought it was because I was undesirable or wasn’t beautiful. I really wholeheartedly believed that for the majority of my upbringing. That started to shift when I began to understand my feelings of dissonance between my soul and my physical form. I guess I realised that dissonance is something completely natural and inherent in our human experience. I recognised that our soul is something other than our physical, and as much as they’re connected and reflect each other, they’re not the same thing. As I understood more about my identity and strengthened it outside of my body, my relationship with my body shifted. That shift allowed me to appreciate my body from a different perspective, as opposed to what I was doing before, where I was like, “Oh my God, everyone’s judging me based on this physical thing.”

E: What about your sexuality?

My sexuality hasn’t so much affected my body image, but my gender identity definitely has. Relating to the physical, I suppose that gender presents its own difficulties. I mean, there are elements of my physical body that don’t align with my gender identity, at least in socially acceptable ways. Having breasts is something that I constantly struggle with. But that being said, it’s also somewhat liberating - it’s also really helped me understand how my physical body doesn’t represent me in my entirety. In fact, it’s impossible that it could represent me in my entirety. That’s something I’ve learnt as a non-binary genderqueer person, whose gender identity is constantly fluctuating.

E: How has your cultural background influenced your body image?

I only realised that I wasn’t white when I was about 18 years old.

I went to a private Jewish school where the majority of students were of South African background. There were like, three other brown kids in my year, and we’d joke about being the only brown kids. I didn’t actually register that I had a different cultural background to everyone else until I graduated school. And I think that’s sort of empowered me.

I guess for a long time, I got by with enough privilege to not be reminded constantly of the colour of my skin, which definitely has its pros and cons. I mean, at school I was really confused as to why no one found me desirable. I can now reflect on that and be like, oh, racial bias and the “otherness” of being a brown-skinned person. Whether it was conscious or not, I think young [white] children, especially from conservative backgrounds, are quite intimidated or afraid of brown bodies. But I mean, it’s only added another layer of complexity to my relationship with myself. At this point, I find being brown quite empowering and something that I really value and cherish about myself. The more I lean into my otherness, and the more I lean into my differences and the things that make me unique, the more affirmed I feel in my body.

Do you see yourself represented in the Australian music industry?

Definitely not. There is a really huge dissonance in what the Australian industry claims to want and what it actually practices. There’s a lot of talk about being intersectional and wanting to be diverse and all of this stuff, but in practice, it just misses the mark entirely. And it’s not for lack of artists of diverse genders or cultural backgrounds - perhaps it’s just because of what’s the easiest and most accessible. You know, there’s these cis white, skinny, surfer-dude bros who make that one very generic kind of music that apparently the Australian public can’t get enough of. I believe they have room for more.

E: How does that make you feel?

It’s really disheartening. There’s definitely a big part of me that wonders why I’m doing this if I’m only going to tick the “token, gender-diverse, brown person” diversity box. And I mean, that’s happened and partly why I think I’ve had many of the opportunities I’ve had. I’m pretty sure it was just to save face and to not get called out. You know the whole @LineupsWithoutMales thing? Like, festivals making sure they hit a 50/50 [gender] ratio? It’s upsetting, but also something that keeps me going - it gives me a reason to represent.

Are we on a road to changing this?

I mean, the fact that there’s this desire to save face and a pressure to meet those quotas is something. I think we are on the road to a more diverse musical landscape in Australia and the mainstream, but I think it needs to come from the genuine intention of being accepting and encouraging of all kinds of musicians as opposed to the intention to not get fucked on by the public. I don’t know if that intentional shift is something that we’re close to at all. But I have hope. I mean, I have to have hope, right?

Where do you look to see yourself represented?

It’s really hard. I find safety and familiarity in my own community and see myself represented there, but in terms of the music scene and public figures, I think I’ve gotten to a point where I recognise I won’t find that representation. I certainly don’t look for representation in so-called Australia - that type of representation doesn’t exist in an accessible way here. There’s some folks I follow on Instagram, but they’re from other places across the globe. And I don’t follow those people to see myself represented anyway. I’ve never thought about looking for myself in musical role models because it’s never an option. It’s kind of sad.

How has your body image impacted the way you present yourself as an artist?

In the past, I tried to dull things down and make myself more palatable. I never really allowed myself to realise my creative impulses because I didn’t think they would be desirable or attractive to the mainstream, or even just the music scene. Unfortunately, I think that’s still pretty true. That being said, I haven’t really been doing much music stuff this year. I’ve been focussing on personal growth and implementing structural changes to the ways I engage with my artistry and musicianship. I’m quite excited to bring a new element of myself to the music scene when we start back up again - an unapologetically fearless declaration of who I am in all of my intersections, showing the industry how implementing diversity quotas are not the only thing people need to do to feel comfortable. I’m actually tired of making sure that people are comfortable around my presence. In future, I’ll be a lot louder.

Have white beauty standards had any implications on your artistry?

100%. I mean, I’ve tried very hard to maintain my artistry as authentically as possible, but white beauty standards have still had an incredibly damaging effect on my perception of self, which only now, at the age of 23, am I starting to unravel. Only now I can be honest with myself about what those effects have been, what I need to do to work through them, and how to shift those thought patterns.

For the longest time, white beauty standards made me hate myself. With a Middle Eastern background, I’m hairier than most people, my hair is a bit more coarse, I sweat more, my skin is darker. For the longest time, I thought all of that meant there was something wrong with me. For the longest time, they were things I couldn’t accept, couldn’t celebrate. I tried to change these things. I didn’t even understand that these things were a result of just my genetics. Of course, now I’ve started this journey of unlearning and reprogramming, that’s really different. It’s starting to shift now. I’m working through it. We’re working through it.

E: Yeah, I think we’re all trying to recondition ourselves out of these really awful and destructive ideals.

Yeah, white beauty standards don’t just have negative impacts on non-white people. They’re fucked for pretty much everyone because they’re unrealistic. Whether it’s weight-based, clearness of skin, whatever… what is advertised as “normal beauty standards” is unattainable to most. It’s not even real. It’s photoshopped and digitised. It’s something that we all need to actively be deconstructing. Especially for non-white people, but also for everyone.

Should we be talking about body image when there are more pressing social and political issues?

It’s all deeply connected. You can’t talk about white beauty standards without talking about racism. You can’t talk about global warming and environmental justice without talking about Indigenous sovereignty. And I think if someone is passionate about deconstructing white beauty standards, it’s up to them to consider whether or not it’s their place to be spearheading that discussion. Secondly, if it is their place, then it needs to be intersectional and carry an awareness. For example, in this conversation, yes, we’re talking about white beauty standards, but there’s also the space to engage in a whole host of other political content. I think that’s really necessary when discussing any sort of political or social matter.

So, is there space for discussing body image issues when the rest of the world is so deeply cooked as well? I guess there has to be. It’s part of deconstructing the inherent societal flaws and toxic patterns of “normalised behaviors” that we’ve been force-fed since popping out of the womb.

How has your identity affected the way you’ve been treated in the music scene in so-called Australia?

There have been opportunities given to me just because of my “identity”: the labels that I choose to give myself to cope with existing. There have been times where I’ve found really amazing people in the industry because of our similarities in our identity, because of our differences. There have been countless times where I’ve been completely overlooked at shows or festivals. I was very much just there to be there. When you invite someone to perform at your show, what kind of support have you put in place to make sure their experience wasn’t personally damaging? If their experience was damaging, do you have a process of accountability and can you make the appropriate reparations?

That type of support simply just does not exist. At all. And there have definitely been times where I deeply wish that it did. I’ve had many experiences where I’ve been encouraged to quieten myself. I’ve been encouraged to make myself smaller and keep my head down - to keep it all as vanilla as possible and to be easy to deal with. There have been times where it hasn’t mattered how loud I am - the people in charge don’t have any intention of actually listening to me and my needs.

Normally, if someone isn’t part of the queer community, I can sense their fear when they engage with me. It’s as if they’re afraid of doing the wrong thing. If you’re a booker and you are inviting me, a gender diverse person, to perform in your space, it really doesn’t take much to make me feel safer.

The first step is to stick up a couple pieces of paper over gendered bathrooms (eg. this bathroom has a urinal and this one does not). You can also just ask me what I need to feel safe. “What does Imbi need to feel comfortable?” And for sure, that doesn’t have to be exclusive to gender - that support should be provided when you’re inviting anyone into your space.

Unfortunately (and more often than not), people think they’re being inclusive just by inviting those [gender diverse] people there to play, and think they don’t have to do these other things. It’s so upsetting. You need to realise that you’re inviting someone whose day-to-day existence entails dealing with being overlooked, misinterpreted, misunderstood and oftentimes attacked.

E: What about as a person of colour?

While I think my experiences are valid and real, I’m quite light skinned and definitely don’t cop the brunt of racism in any way, shape or form.

Could you elaborate on your experiences of skin colour bias?

It’s really challenging to discuss and to navigate because I have faced microaggressions where it’s quite obvious that the white people in the space are being treated substantially differently and given different preferences. That being said, when I’m in a space with darker-skinned people, that same amount of privilege that’s granted to white people is then granted to me.

That’s a process of accountability that I have to take on.

I have to recognise where that privilege comes through, what I can do with that privilege to ensure the person perpetuating the racial bias is aware of what they’re doing, and then make reparations for that. If I haven’t stood up in the past, which has happened, then it’s me sitting down and thinking, “Okay, how can I make reparations for my head nodding where I should’ve been shaking my fist in solidarity with those who look a little bit different to me?”

These are really important conversations. People find it hard to admit that they’ve done something wrong, but that’s just a part of the human experience. We all have done many things wrong. It’s about learning what each situation asks of you and taking accountability.

Do you feel you’ve seen many incidents of colourism in your time in the music industry?

Yes, I do. Many times. And I don’t see that changing anytime soon - I see it as something that’s very deeply ingrained in the so-called “Australian” psyche: a systemic problem. The entire social structure and system here is based off mass cultural genocide and white supremacy. In order to amend the toxic behaviours people have been perpetrating for decades, there requires an entire deconstruction of what is considered “normal behaviour”. If we want our planet to live on, we have to decolonise. I don’t know if people are ready for that conversation yet?

What change would you like to see in the so-called Australian music industry over the next five years?

In an ideal world, I’d like to see reparations made. I’d like to see diverse and intersectional lineups at every event. I’d like all Indigenous lineups at festivals that are celebrated and encouraged by the mainstream. I’d like to see new levels of safety and community care implemented throughout venues and festivals. I’d like to see less white men running venues and festivals. Being realistic, furthering discourse. I’d like to see more of these conversations going on in more mainstream ways. It’s not hard to put up a poster at a venue that says “if you feel unsafe, do this”.

I hope the industry can change and grow. I really do. I hope that the widely accepted norms within the music industry can be deconstructed and reconstructed in more equitable, accepting and intentional ways.

I’d also like to say that I hope people can be gentle with themselves in taking accountability. I’d like to express my deep love and care for the people who’ve engaged in this, either as readers or as people helping to push these sorts of conversations. I hope everyone can love themselves and their communities. Only then can we all grow together.

Keep up to date with Imbi here

We would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri people who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live, and recognise their continuing connection in our community. We would like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present of the Kulin Nation and extend that respect to other First Nations people who have read this article.

Comments